Jewish summer camp is such a crucial part of the American Jewish experience that many Jewish adults, even in their older age, likely remember the names of many of the kids in their cabins from when they were 11 years old.

Jewish summer camp is such a crucial part of the American Jewish experience that many Jewish adults, even in their older age, likely remember the names of many of the kids in their cabins from when they were 11 years old.

One of those cabins more than 60 years ago contained a couple of interesting young Jewish boys.

Louie Kemp would go on to head his family’s seafood company and played a key role in introducing imitation king crab to the United States. Robert “Bobby” Zimmerman, went on to become Bob Dylan.

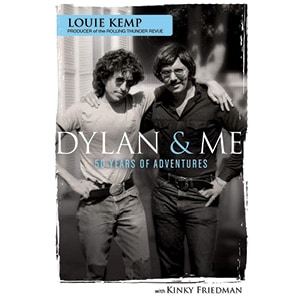

Kemp has now written a memoir called Dylan & Me: 50 Years of Adventures, detailing his decades-long friendship with the iconic singer.

The journey begins when they were preteen campers at the Jewish Herzl Camp in Webster, Wisconsin, from 1953 through 1957. In ’54, Kemp witnessed a cabin rooftop concert that he considers the then-11-year-old Bobby’s first public performance.

Following the stories of summer camp concerts and hijinks, the book follows Dylan and Kemp’s time together as teenagers in Kemp’s hometown of Duluth, Minnesota, where Dylan was born, and later in Minneapolis, where Kemp attended college and Dylan briefly moved to pursue music.

Even after Dylan went to New York and became one of America’s most famous men, they continued their friendship. Kemp frequently stepped away from his lucrative business, which sold fish to the restaurant industry, to hang out with Dylan for weeks at a time in the city, Malibu, Mexico or wherever the singer was on the road. Dylan was the best man at Kemp’s wedding.

Kemp says he hadn’t always intended to write a book about his friendship with Dylan, but he had been telling the stories at parties and Shabbat dinners for years and was told frequently that he should collect them.

“After a while it dawned on me—these were special stories,” Kemp says.

A close friend of Kemp’s—a former television producer who was dying of cancer—made him promise to write the book, so he agreed. Kemp didn’t want to break the promise once the friend passed away.

Kemp produced Dylan’s famous Rolling Thunder Revue tour in 1975 and ’76, and his remembrances—about the nontraditional lineup and promotional structure, and concerts featuring several famous guest musicians—take up much of the book’s middle section. The tour was the subject of a slightly faux-documentary, Rolling Thunder Revue: A Bob Dylan Story by Martin Scorsese, which debuted on Netflix earlier this year.

Kemp appears a few times in vintage footage in the film. A talking head describes him as “a longtime friend of Bob’s and a fishmonger” before declaring that Kemp was “out of his element, unprepared and wasn’t too well-liked on the tour.”

However, the person who says that, Jim Gianopulos, playing the part of “The Promoter,” wasn’t actually involved with the tour—he was one of several fictional characters Scorsese invented for the movie.

Kemp says he enjoyed the documentary, especially the live footage of the musical performances, which feature what he described as “Bob in his prime.” But like a lot of people, he noticed that some things in the film weren’t what they seemed.

“Bobby and Marty decided to spice it up a little bit and be tricksters,” Kemp says about the fictitious flourishes. “So they put in four bogus talking heads. When I saw it [I said] ‘who are these people? They weren’t on the tour!”

He also challenged the film’s implication that the Rolling Thunder Revue tour was a money-losing endeavor.

Kemp lived with Dylan for a time in Los Angeles in the early 1980s during the period when Dylan briefly became a Christian. Kemp, who at the time was beginning to become a more observant Jew, which he remains to this day, claims credit, along with some rabbis, for bringing Dylan back into the Jewish fold a couple of years later.

The book is full of delightful, specifically Jewish details, such as the time Kemp and Dylan attended a seder at a Los Angeles synagogue with Marlon Brando (Brando, like Frank Sinatra, was an Italian American who was known for his love of the Jewish people). There were also Dylan’s years of participation in Chabad telethons, the time he opened the ark on Yom Kippur while being mistaken for a homeless man and the story of how Kemp arranged for Kaddish to be said for Allen Ginsburg each year on his yahrtzeit. All that, and many, many visits to Canter’s Deli.

Dylan wasn’t Kemp’s only famous Jewish friend. Among those thanked in the book’s acknowledgements is Larry David, a one-time neighbor of Kemp. (“You can’t move! You are the best neighbor I have ever had—even better than Kramer!” David said, according to the book.)

In the book, Kemp talks specifically about how he believes Dylan’s Jewish background informed his later success.

“[Jews] have a passion to seek out meaning and give it new expression, morally and artistically,” Kemp wrote. “That drive—along with another Jewish trait known as chutzpah—have always been strong in Bobby, and his gifts have made his expression worthy of the ages.”

“Growing up in a Jewish household kind of instills in you a tendency to be pro-underdog because for so many years we were suppressed,” Kemp says.

Herzl Camp, where it all began, has taken notice of Kemp’s book.

“Part of our mission is to build lifelong Jewish friendships, so it is wonderful to see the story of a group of camp friends and how their friendship spanned decades,” Holly Guncheon, the director of development for Herzl Camp, says. She adds that Dylan sent his children to the camp.

At Herzl, like many camps, campers write their names on walls for posterity, and Guncheon says that “for many years, searching for ‘Robert Zimmerman’ written on a cabin wall was a common activity.”

While the two men, now both in their late 70s, have known each other for more than 60 years, the book’s subtitle is 50 years of adventures, and it’s notably missing any stories from after 2001. Kemp admits that he and Dylan have lost touch of late, although he says it wasn’t due to any particular falling out, and he did send Dylan a copy of the book.

“I would think he’d enjoy it, it’s all positive, fun adventures that we had together over a 50-year time period,” Kemp says. “To me, it’s like a modern-day Jewish version of Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn.”

Stephen Silver