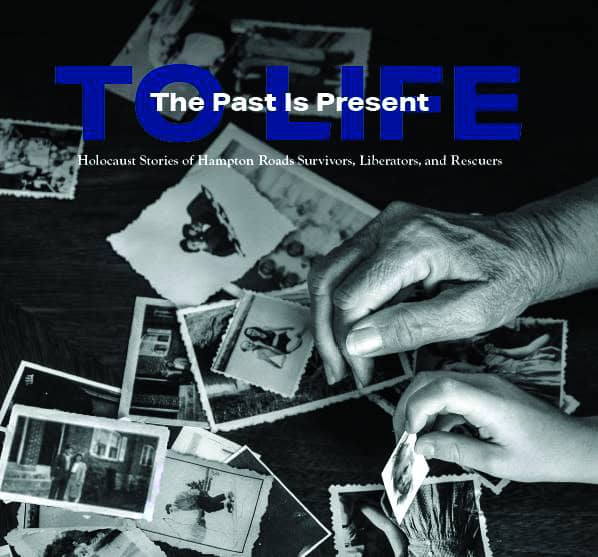

Earlier this year, the Forward wrote about the Holocaust Commission of the United Jewish Federation of Tidewater’s book, To Life: The Past is Present, including six of the publication’s stories. The article, with two of the stories, is reprinted here with permission.

They survived harrowing Holocaust ordeals — and found extraordinary new lives in the U.S.

Stories highlight the lasting trauma of the Shoah — and the ways survivors came to thrive, afterward.

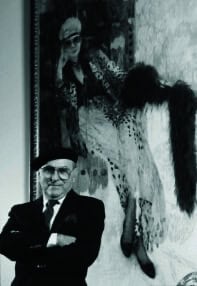

Camillo Barone

Jewish children hidden in Catholic orphanages in Belgium; parents and grandparents forced to choose which of their children to save in Polish ghettos; entire families hidden for months in underground tunnels in Ukrainian cities.

To Life: The Past is Present, a revamped edition of a book first published 21 years ago, features over 90 stories from Holocaust survivors, liberators and rescuers, all united by one detail: They all ended up in Coastal Virginia.

The Holocaust Commission of the United Jewish Federation of Tidewater in Virginia recently reissued the book.

Frank Shatz

In 1944, Frank Shatz was deported to Romania by the Nazis, and sent to perform forced labor to build a railroad line over the rugged Carpathian Mountains.

“We were treated just like animals. If we dropped a rail and crushed another worker’s leg, the Nazis would shoot him,” he said. “He no longer had value to them.”

One day, as the Allies were bombing Romania, Shatz managed to escape to Budapest, Hungary, where he was hidden in one of the “safe houses” established by Swedish diplomat Raoul Wallenberg. Some days later, he joined the Zionist underground and was provided with false identity papers.

He eventually fled communist Czechoslovakia with his wife Jarka in 1954; both were active members of the anti-Communist underground. They eventually settled in Lake Placid, N.Y., where Shatz founded a successful leather company, before moving to Williamsburg, Virginia.

The Virginia General Assembly has twice honored Shatz for sharing his story of survival and his commitment to Holocaust education in Virginia.

Esther Wondolowicz Goldman

Goldman’s childhood in Sokoly, Poland was a happy one. But the invasion of Poland by Germany in 1939 thrust Esther and her large, Orthodox family into a world of fear and secrecy. After their house was burned down on Erev Rosh Hashanah in 1941, they went into hiding in a cemetery, before eventually being caught and sent to concentration camps like Birkenau and Auschwitz.

“We didn’t know what they were going to do to us, but then they spoke and told us to forget our names, that we no longer had names and, from this day forward …we ceased to exist, other than as a number. I became 34838,” she said.

The memories of the atrocities she witnessed, including the burning of children, haunted her throughout her life. After surviving a death march to Ravensbrück, she returned to Poland.

There, she crossed paths with her older brother, Iser, who had survived the war as a partisan fighter. Seeking refuge, she relocated to Bialystock to reside with him and his newlywed wife.

They then moved to Lódz´ , where Esther encountered Chil Goldman (later known as Charles), her future husband and fellow concentration camp survivor. They married in November, 1945.

Eventually, Esther immigrated to the U.S. in 1957, where she worked as a tailor and seamstress and built a new life with Charles. She was an active educator about the horrors of the Holocaust throughout her life, and died on December 14, 2001.