On April 12, 1945, General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Supreme Commander of the Allied forces in Europe, accompanied by United States Generals George S. Patton and Omar Bradley, toured the Ohrdruf concentration camp, the first camp to be liberated by US forces after WWII. Nothing could have prepared them for skeletal survivors too weak to move or the stacks of bodies sprinkled with lime that did little to mask the intense odor. General Patton, who had witnessed many war atrocities, was so overcome by the stench and devastation that he vomited by the side of a building.

Eisenhower later wrote, “I have never felt able to describe my emotional reactions when I first came face to face with indisputable evidence of Nazi brutality and ruthless disregard of every shred of decency. Up to that time, I had known about it only generally or through secondary sources. I am certain, however, that I have never at any other time experienced an equal sense of shock.”

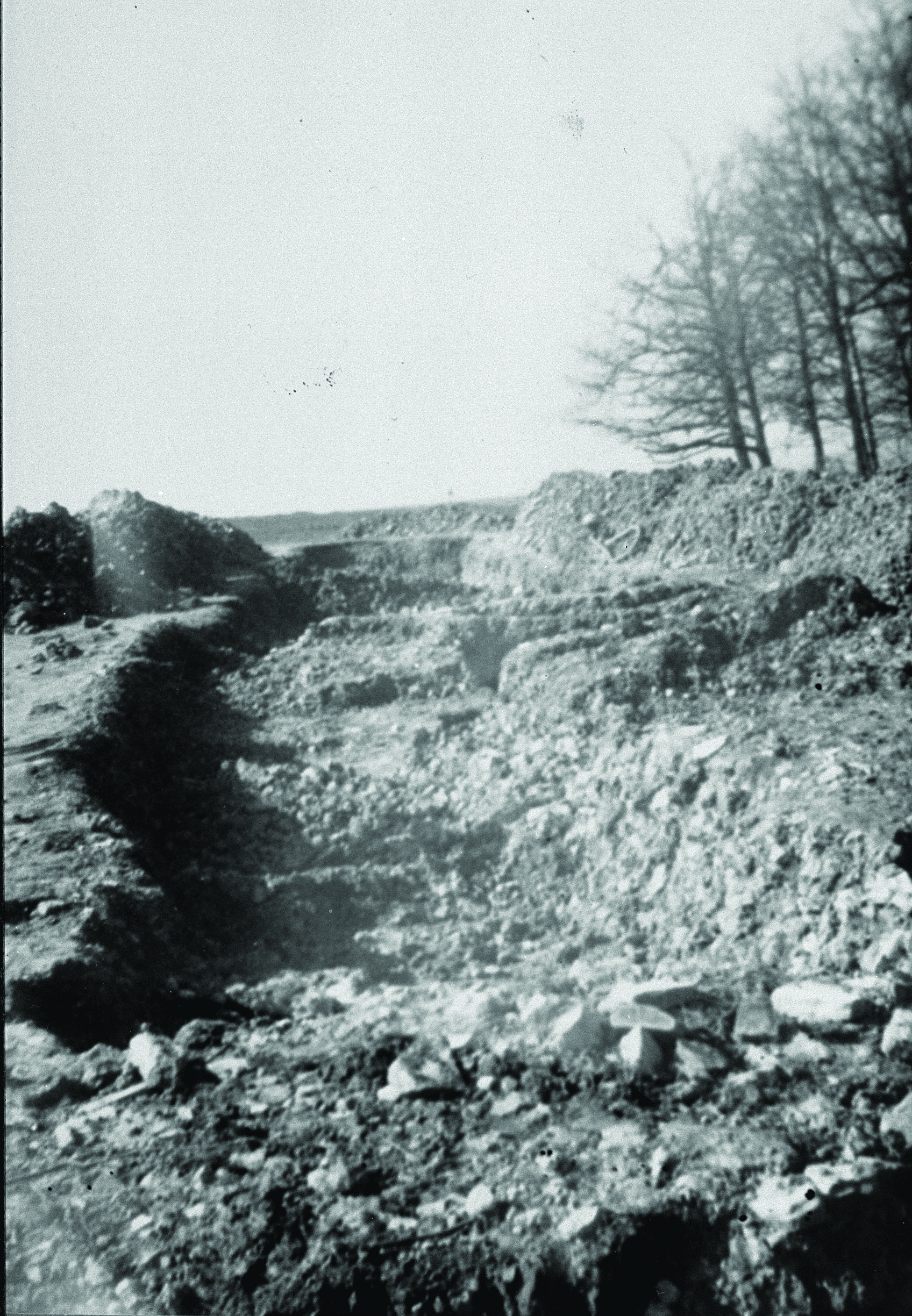

After his tour, Eisenhower immediately realized the need to document the brutality perpetrated by the Nazis and foresaw the era of Holocaust denial. He ordered Army photographers to record the unimaginable and horrendous evidence so that it could not be reimagined as Nazi “propaganda,” laying out to the world the danger of unchecked racism.

Eisenhower insisted that everyone under his jurisdiction saw these camps. He commanded Germans living in the surrounding areas and any U.S. soldier not fighting at the front to walk through the camps to witness these atrocities for themselves. The media was also given generous access so that these images soon appeared around the world.

This archive of film and photographs illustrated what was defined at Nuremberg as “crimes against humanity” at the most visceral level when presented together with eyewitness accounts and other evidence. Even those on trial found them shocking. Over 80 years later, these images serve as an important archive documenting the atrocities of the Holocaust. Visual images transport a viewer to a scene. When we watch these films, we see what Eisenhower saw and become witnesses ourselves.

Sadly, Holocaust denial started almost immediately at the Nuremberg Trails in 1946. Hermann Goring, among others, although pleading guilty, still attempted to whitewash his war crimes during the Third Reich.

In the following decades, even when confronted with visual evidence and eyewitnesses, Holocaust deniers have continued to either deny that the Holocaust took place or diminish its extent through a host of conspiracy theories, sometimes masked as legitimate scholarship.

No community is immune. In the fall of 1986, the United Jewish Federation of Tidewater had the privilege to host the first stop in the United States for a special exhibition: “Auschwitz: A Crime Against Mankind.” The exhibit, sponsored by the United Jewish Appeal, the World Jewish Congress, and the Polish Government, had previously been at the United Nations. Curated by the Auschwitz State Museum and the International Auschwitz Committee, the exhibit displayed 135 photographic panels and 80 artifacts chronicling one of the largest killing centers of the Holocaust. City and business leaders, college and university presidents, school superintendents, social studies coordinators, and hundreds of Jewish and non-Jewish community members visited the exhibit.

Several weeks later, a small group arrived with no intention of viewing the exhibit; the Christian Identity Movement was there to protest and deny the Holocaust. Their signs read “Why do they lie?” and “Zionist Jews are traitors to Christian America,” and they handed out pamphlets attacking the historical foundations of the Holocaust and Jews in general. In solidarity with the Jewish community, 500 people from all sectors of Hampton Roads listened to a roster of speeches denouncing the deniers protesting outside. While the rally attendees were told to ignore the protestors, the media did not. Esther Goldman, a local Holocaust survivor and docent for the exhibit, was watching this on the news and was enraged. Before her family could stop her, she drove to the Jewish Community Center, rolled up her sleeve to expose her tattoo, number 34838, and confronted the deniers. “Let anyone tell me it didn’t happen,” she said.

Even when confronted with artifacts, documents, and an eyewitness, these deniers still insisted that the number of Jews killed was “closer to 100,000” and that what is commonly believed is incorrect because “all major publishing firms and the mass media are Jewish-owned.” Nearly 40 years later, these arguments are still part of an arsenal of antisemitic lies now amplified by social media, and there are very few eyewitnesses alive to tell their own stories.

Facts, documentation, and education are the best tools to ensure that Holocaust history is taught widely and meaningfully. In the 21st century, technology offers many new threats to what is factual. By far, the images General Dwight D. Eisenhower insisted on recording in 1945 have stood the test of time and are still foundational to revealing what can happen when hate is not stopped.

1 Dwight D. Eisenhower, Crusade in Europe;(New York; Doubleday, 1948), 408.

2 Dwight D. Eisenhower, Crusade in Europe;(New York; Doubleday, 1948), 409.

3 Steve Stone, “Protest Challenges Holocaust Exhibit,” Virginian-Pilot. September 26, 1986.