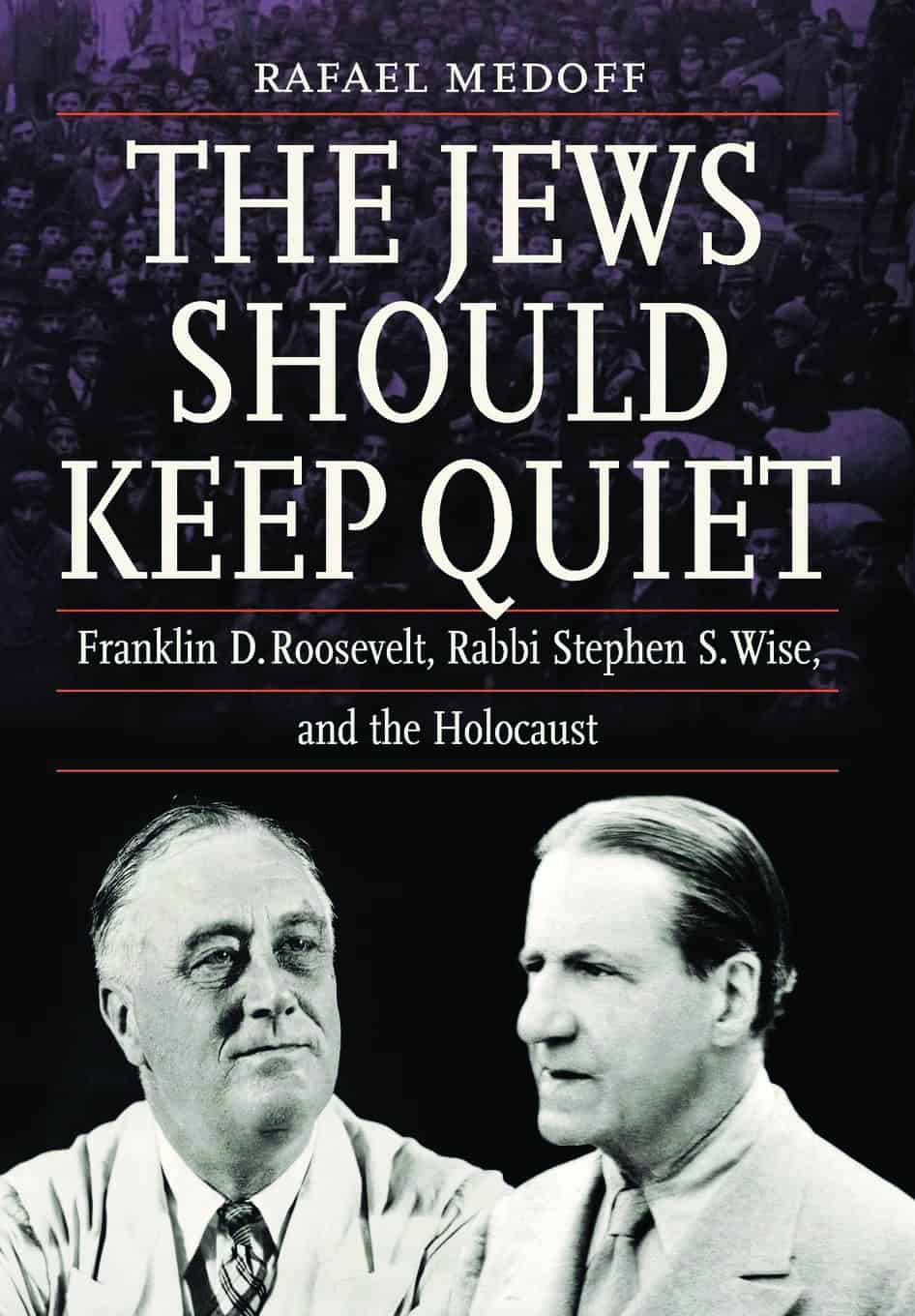

Rafael Medoff

Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society, 2019. 387 pages.

Professor Rafael Medoff is an orthodox ordained rabbi and prolific author who is the founding director of the David S. Wyman Institute for Holocaust Studies as well as the co-editor of its online Encyclopedia of American Response to the Holocaust. The Jews Should Keep Quiet is dedicated to the late Wyman whose breakthrough 1984 book, The Abandonment Of The Jews, charted a pioneering and courageous path of consequential and painful realities in confronting the Shoah’s monumental dimensions.

The revealing new material helps demonstrate beyond a doubt a direct link of FDR and Rabbi Stephen S. Wise whose joint policies and assertions of commission and omission, contributed to an overwhelming calamity for the Jewish people and humanity. Medoff succeeds in debunking long-held views such as that FDR, who was practically worshiped by adoring American Jews for his New Deal, cared for Jews and their preeminent leader, Rabbi Wise. Emerging is a Machiavellian plot to cynically outmaneuver a naively trusting Jewish leader who was enamored by a clever president who bestowed upon Wise and his family tokens of friendship and gratitude, ensnaring Wise to believe that FDR would not betray him and even more critically, a vulnerable European Jewry in Hitler’s devouring clutches.

In fact, unwittingly or not Wise enabled FDR, a master manipulator in his constant intimidating harangue “that he wanted the Jews to keep quiet” and their obeyed silence would best serve to save fellow Jews and even protect American Jews in a highly antisemistic society which by 1940 had more than 100 antisemitic organizations with the vast popularity of the antisemitic Catholic priest, Father Charles Coughlin. Isolationism, Nativism and following the Great Depression and high unemployment, as Medoff’s points out in FDR’s defense, weighed on him while also burdened with WWII preparations. Thus, Wise did all in his substantial power to enforce Jewish fatal inaction as leader of the major Jewish organizations: The American Jewish Congress, which he founded to neutralize the then anti-Zionist American Jewish Committee- The World Jewish Congress, the Jewish Institute of Religion that he founded and later merged with Hebrew Union College. He was also chief editor of the magazine, Opinion.

To aggravate matters, FDR’s mom, Sarah, and other family members were unabashedly antisemitic. FDR himself was proud of his family being devoid of “Jewish blood.” He explained away Polish antisemitism to the dismayed Wise, that it resulted from Jewish prominence.

How reason the 1939 sordid affair of FDR turning away the SS St. Louis though the US Virgin Islands offered safe haven to the 937 desperate fleeing Jewish refugees? How understand that FDR opposed, aiding, and abetting a notorious antisemitic State Department, in 11 of his 12 years in office (1933–1945) to fulfill the quota for Germany, and his refusal to accept 20,000 Jewish German children? Vice President Henry Wallace quotes Secretary of War Henry Stimson that the State Department is “the wailing wall for Jews.”

Three days before Yom Kippur on October 6, 1943, the first Jewish march on Washington took place with more than 400 Orthodox rabbis participating to Wise’s chagrin. Organized by the Bergson Group, this massive demonstration of very traditional rabbis in practice and appearance, who spoke Yiddish and represented a distinct old world Jewish flavor, made Wise and fully acculturated American Jews very uncomfortable, concerned of how non-Jews would react. This impressive turnout of spiritual leaders on behalf of their millions of European brethren, sought to pressure FDR’s Administration to create an agency focused on rescuing the Jews from extinction. Fearing embarrassment and worse, FDR chose the meek approach of avoidance and refused to even meet with the rabbis’ delegation.

It was only under the cloud of a likely adoption of a Congressional resolution to firmly support Jewish refugees and with a pending election, did FDR agree to reverse course and establish the War Refugee Board on January 23, 1944. Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau Jr., the only Jew to ever serve in a FDR cabinet, was instrumental in FDR’s long-coming acquiescence in saving Jewish lives. Yet, the tragic delay amounted to a loss of more than four million Jewish lives and 440,000 Hungarian Jews. Medoff emphasizes that since the WRB managed to save 200,000 Jews and 20,000 non-Jews till the war’s end in May 1945—numbers that pale in comparison to the vast losses—is proof that had the WRB been established earlier it would have made a significant difference. FDR’s Administration’s mantra with Wise buying into it, that Jewish rescue should await Nazism’s defeat, proved to be false and disastrous.

Liberty ships transporting American troops to Europe and returning home empty, could have carried refugees. The failure of responding to Jewish pleas to bomb the railways and bridges leading to Auschwitz and the murder of 1.1 million Jews, in the guise that aerial military operations took precedence, has no justification. Allied planes dropped bombs on enemy oil and chemical installations nearby. On August 20, 1944, a major American bombing campaign raided a target five miles from Auschwitz with the participation of the famed African American Tuskegee Airmen piloting 100 Mustang fighters. Sixteen-year-old prisoner Elie Wiesel witnessed it with joy and later bemoaning in his classic Night, that no bombs rained on Auschwitz.

Wise is blamed for his inability to free himself from his all-consuming allegiance to FDR. Perhaps, muses Medoff, Wise’s increasing health issues were a factor. A persisting puzzle—to what extent was FDR and for that matter Rabbi Wise victimized products of their times, and to what degree did they fail to rise above their times and make a critical difference?

Following the February 1945 Yalta Conference, FDR met with Saudi Arabia’s King Ibn Saud aboard the USS Quincey, at which both of them nixed the revival of Jewish life in Palestine. It is safe to conjecture that had FDR been in office in 1948, he would not vote for the declared Jewish State. Already in spring 1938 the both visionary and practical David Ben-Gurion called FDR “an anti- Zionist.”

In his 1949 autobiography, Challenging Years, Wise seals his positive evaluation of FDR with glowing words, though Medoff interprets it as opening a window for potential criticism of his idolized hero. Thus, Wise seeks to defend his own blemished record that cannot be separated from FDR’s indefensible record. “’It is in his rendezvous with destiny that he was equal to its measureless and majestic responsibility. Woe to them who vainly sought and seek to divert this heroic figure from his definitely appointed rendezvous.’”

Medoff concludes, “He (FDR) saw America as “a Protestant country” with “the Jews” and people of other backgrounds present only “on sufferance.” Perhaps, then, it is not surprising that he was disposed to policies that would exclude, restrict, dispense, or silence such minorities. To stifle Jewish criticism of these policies, Roosevelt exploited the insecurities of a mostly immigrant and not yet fully accepted community and maneuvered Rabbi Wise to help endure that the Jews would keep quiet.”

Rabbi Dr. Israel Bobrov Zoberman is founder and spiritual leader of Temple Lev Tikvah and is Honorary Senior Rabbi Scholar at Eastern Shore Chapel Episcopal Church. He and his family of Polish Holocaust survivors lived from 1945 until 1949 among refugees in Kazakhstan (USSR), Poland, Austria, and Germany.