The Passover seder gets a post-Oct. 7 rethink.

(JTA) — As the American Israeli poet Marty Herskovitz thought about the upcoming Passover holiday, the prospect of singing Dayenu at the first seder since his country was attacked didn’t sit right with him.

The classic Passover song, whose title means “It would have been enough,” expresses gratitude about how much God has done for the Jewish people. But Herskovitz, the son of a Holocaust survivor who has lived in Israel since 1986, thought the words would ring hollow at a time when so many Jews are at risk.

“We have to take the text and find a way to make it relevant and not just say the words that seem so impossible to say,” Herskovitz says. “‘Dayenu, it’s enough.’ It’s clearly not enough. As long as people are trapped in Gaza, that’s not enough. As long as our soldiers are still risking their lives, it’s not enough. We can’t say ‘Dayenu.’ It can’t be, you know, ‘Praise God for this situation.’ So we have to find new texts.”

It’s a mission that has long animated Herskovitz, who used the financial reward from a legal settlement after his then teenaged son was injured in a terrorist attack in 2001 to create a fund to support education initiatives in Israel. The fund has backed his own Creating Memory initiative at Bar-Ilan University, which focuses on Holocaust remembrance through art, and Israel’s Conservative Schechter Rabbinical Seminary.

At Herskovitz’s urging, Schechter convened dozens of rabbis and Jewish community leaders from across Israel earlier this year to reimagine the haggadah, the core text of the Passover seder. The result of their work will be a supplement for Israeli families to use during their seders at the beginning the first major holiday since Hamas attacked Israel on Oct. 7 — an assault that itself pierced the observance of a Jewish holiday, Simchat Torah. (The Oct. 7 attack reportedly had originally been planned for the first night of Passover last year.)

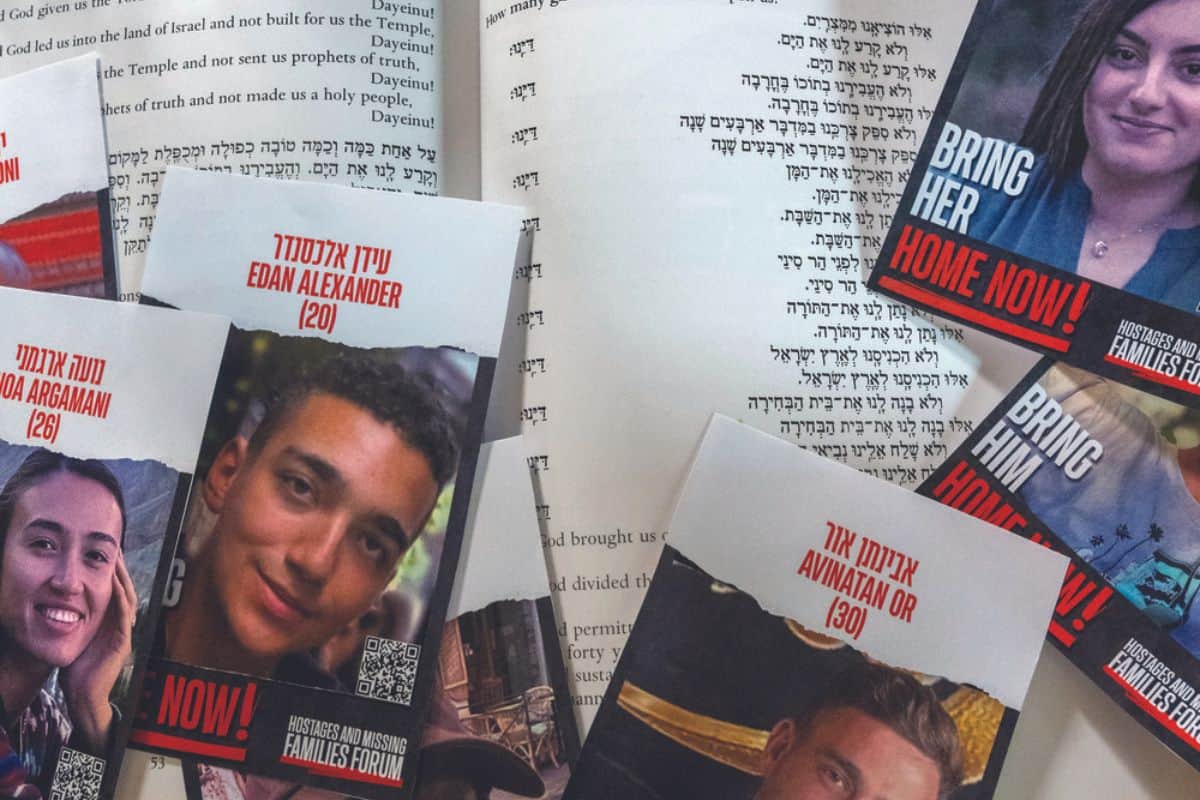

Many seder tables will have empty seats representing Oct. 7 victims, hostages, and soldiers who are unable to return home for the holiday. But the seminary sought to provide rabbis and their communities with other ways to adapt the ancient tradition to the current moment.

“The Passover holiday is really one in which families celebrate on their own,” says Rabbi Arie Hasit, Schechter’s associate dean. Passover is going to happen in the home. So, our job right now, which is so significant, is to help people navigate how to prepare.”

Among the supplement’s passages is an addition to the seminal “Four Questions” recited during the seder, which ask, “Why is this night different from all other nights?” The added text aims to reflect the feelings of seder attendees this year.

“On all other nights, we think that we have answers. Tonight, we all just stay silent,” says the passage, which is in Hebrew. “On all other nights, we remember, sing, and cry. … On this night, we only cry.”

The initiative is one of several underway to adapt the Passover holiday for a different crisis in the Jewish story.

Rabbi Menachem Creditor, the scholar-in-residence at UJA-Federation of New York, is working on a haggadah supplement with the Academy of Jewish Religion, a pluralistic rabbinic school in Yonkers, New York.

“To talk about liberation when our family is not yet whole again is very hard, and our own tears will mix with the maror,” Creditor says, using the Hebrew word for the seder plate’s bitter herbs. “We won’t need the haggadah’s usual explanation of what bitterness feels like.”

Creditor says AJR’s CEO and academic dean Ora Horn Prouser approached him with the idea of creating a Passover supplement about the ongoing Israel-Hamas war. They put out a call for submissions — prayers, essays, artwork, and other reflections — and received dozens of responses that will be edited into a resource AJR will self-publish and sell on Amazon. Parts of the final product will also be available for free on the seminary’s website.

In addition to Dayenu, Creditor and Horn Prouser point to one particular piece of the Passover text with new resonance this year: “Vehi Sheamda,” the prayer that warns that in every generation, a new enemy will attempt to defeat the Jewish people. This year’s crisis conjures new ideas about both the enemy and how to vanquish it, Creditor says.

“The language in the seder, in the haggadah, is that God will save us,” Creditor says. “But Zionism represents a very different religious posture, which is: We will save us.

“Unfortunately, the first part of the paragraph remains true and was amplified horribly on Oct. 7,” Creditor continues. “The second half of it must be true through the connection that we have, as a Jewish people throughout the world, strengthening our homeland.”

The Passover initiatives in both Israel and the United States add to a long tradition of haggadah iterations and supplements that layer present-day issues onto the ancient text, from those centered around Soviet Jewry to more recent examples, like additions about the Ukraine war and the pandemic. Last year, some families left an empty seat at their seder table in honor of Evan Gershkovich, the Jewish Wall Street Journal reporter who remains jailed in Russia.

“The haggadah is something that developed, and as modern Jews who are dealing with issues of the same themes that have come up again and again in our history, we need to figure out how to make those themes accessible, relevant, real and useful,” says Rabbi Sara Cohen, a Schechter alumna who helped plan the seminary’s conference in Israel.

“We don’t necessarily think of holidays as a time for processing trauma, but because Passover is the first major holiday since [Oct. 7] and because it’s a holiday that the story of which talks about national trauma and redemption, one of the questions is, ‘What is redemption in our day, and are we feeling redeemed, are we feeling free?’’’ Cohen says. “We have to pay attention to the desire to process the trauma and the framework that our tradition gives us for processing it.”

Cohen wrote the additions to the Four Questions that are included in the Schechter supplement. Other supplement passages invoke more explicit war imagery and the sense of bereavement felt by many across Israel.

Hasit acknowledges that beginning the project in early February was a double-edged sword. On the one hand, it provided Schechter with plenty of time to collect responses and work with Herskovitz to put together a Passover resource ahead of the holiday.

On the other hand, the war is evolving daily, and nobody knows what the status of the conflict, or the hostages, will be by late April. But Hasit says no matter what happens, the trauma of Oct. 7 will need to be addressed at the seder table.

“We know that [Passover’s] coming, and we know that it’s going to be different,” he says. “We know that it’s going to include processing everything that has happened since Oct. 7. And no matter what happens tomorrow, and the day after that, none of that is going to change.”

Herskovitz says he views the Passover effort as a cognate of his Holocaust remembrance work, in which he emphasizes the importance of creating fresh, personal materials that people can connect with.

“I think the same exact thing is what has to be done in Pesach this year,” he says, using the Hebrew word for Passover. “You cannot use the same text and the same ideas that you used for years and years because this year is so radically different. And to go back to the old text, the old ideas, is basically making it irrelevant.”