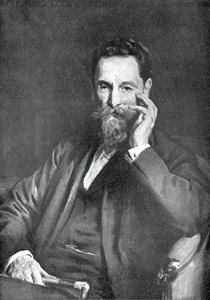

Portrait of United States publisher Joseph Pulitzer, 1918.

LOS ANGELES (JTA)—It’s a story that would not sound too out of place in 2019: New York’s leading newspaper accuses the president of the United States of corruption and the latter sues the paper’s publisher for libel. Striking back, the publisher declares in an editorial that his newspaper “cannot be muzzled.”

That confrontation actually happened in the first decade of the 20th century, pitting President Theodore Roosevelt against Joseph Pulitzer, a Hungarian Jewish immigrant who had lifted The World to the rank of most influential newspaper in New York and the broader United States.

In one of his numerous crusades, Pulitzer charged Roosevelt with orchestrating a $40 million cover-up of corrupt practices in the building of the Panama Canal. Roosevelt retaliated by demanding, in an address to Congress, that the government perform its “high national duty to bring to justice the vilifier of the American people.” Not cowed, Pulitzer proclaimed, “Our republic and its press shall rise or fall together.”

After three years of legal battles, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled for Pulitzer, arguing that even the president was not above the law.

The encounter between the one-time penniless immigrant and the most powerful man in America is but one footnote in the film, Joseph Pulitzer: Voice of the People, which opened March 1 in New York. The documentary on the life of the man who founded newspaper journalism’s most prestigious prize and stood up to the most powerful forces in the country could not come at a more relevant time.

The movie is the latest of some 20 films, mostly documentaries, by Oren Rudavsky. Half of those are on Jewish themes, among them A Life Apart: Hasidism in America and Colliding Dreams, which examines the history and impact of Zionism.

Pulitzer was born in 1847 in Mako, a town on the Hungarian side of the border with Romania, as one of eight siblings. But only he and one brother lived to adulthood.

His first ambition was to become a soldier, and at 17 he migrated to America and immediately enlisted in a German-speaking unit of the Union Army in the final year of the Civil War. Pulitzer’s first postwar job was shoveling coal, but he soon embarked on his journalistic career through a German-language newspaper in St. Louis. On the side, he taught himself law and became an investigative reporter.

In 1881 he struck out for himself and founded the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, pledging to “oppose all frauds and shams,” and promoting a writing style of short, snappy paragraphs.

For starters he published the names of all tax dodgers in St. Louis—and in those rugged days, he was not surprised when his managing editor shot a critic of the newspaper.

Two years later, Pulitzer had accumulated and borrowed enough money to purchase the New York World for close to $400,000, proclaiming the paper’s policy by observing “Accuracy is to a newspaper what virtue is to a woman.”

Around the same time, he married the beautiful Kate Davis, an Episcopalian and distant relative of Jefferson Davis, the leader of the Confederacy during the Civil War. The marriage of a member of the Southern aristocracy to an immigrant Jew apparently was not considered as scandalous as it would be in a later century, Rudavsky noted.

“There was relatively less anti-Semitism in America in the 1870s and 1880s, before the start of the Jewish mass immigration in subsequent decades,” Rudavsky says.

Still, Pulitzer’s numerous political enemies and journalistic competitors referred to the publisher as “Jewseph Pulitzer,” and caricatured him with a huge hooked nose.

Pulitzer used the clout of his newspaper to bring the Statue of Liberty to New York Harbor, to defeat a proposal to charge pedestrians for walking across the newly opened Brooklyn Bridge, as well as to acculturate the waves of new Jewish and other immigrants to the new country. As a permanent legacy, he endowed the Columbia University School of Journalism and the Pulitzer Prize.

During the run-up to the 1898 Spanish-American War, Pulitzer was accused of resorting to “yellow journalism,” in competition with the warmongering Hearst papers. But Rudavsky cited as a more fitting epitaph the appraisal of novelist and newsprint crusader Nicholson Baker, who judged Pulitzer to be “the most original and creative mind in American journalism.”

By Tom Tugend