PROVIDENCE, R.I. (JTA)—The other day, I saw an interesting Facebook post written by a college student who lives in New York. She was looking to find a daily morning minyan. Specifically, she sought one that met at a “college student-friendly hour,” since most minyanim are scheduled for fairly early in the morning while she is still asleep.

A simple response arose in the comments: “Try a shul in the Midwest.”

We cannot lose sight of how thoroughly astonishing a comment like this would seem to Jews of any previous generation, how ordinary it has become over the past two months, and what that shift signifies for the present and future of Judaism. Not only is it possible today for any of us to go to services—every day—1,000 miles away, it’s more possible than doing so at our synagogue down the street.

A few months ago, the digital Jewish ecosystem was relatively sparse. For most institutions, livestreaming a program was rare—the occasional cherry-on-top of the sundae that was in-person Judaism.

In just two months, the norms have flipped entirely. The reason that we need to sit with the astonishing nature of this reality is that it represents a change in the entire Jewish world for the years and decades that will come.

I have worked for a digital Jewish organization for over four years. For five years I’ve been studying to be a rabbi—digitally. For seven years I’ve been a part of Jewish social justice projects that operate largely via video chat, Facebook groups and other digital modalities.

It is exceedingly hard for me to believe that people will simply flip a switch at the end of social distancing and go back to how things were. Once somebody has held a Passover Seder that brings together their grandparents in Arizona, their parents in Houston and their own self in Massachusetts, for free, I don’t think they will be content to gather only with folks who live nearby or can afford to travel in.

The importance of digital Jewish gathering goes beyond that, too. People with disabilities—many of whom have been calling for digital programming for years—will still want and need Jewish experiences that they can enjoy from their homes once this period ends. Jews who have grown frustrated by their local communities, or who live in places without Jewish institutions, will continue to crave digital opportunities for Jewish engagement.

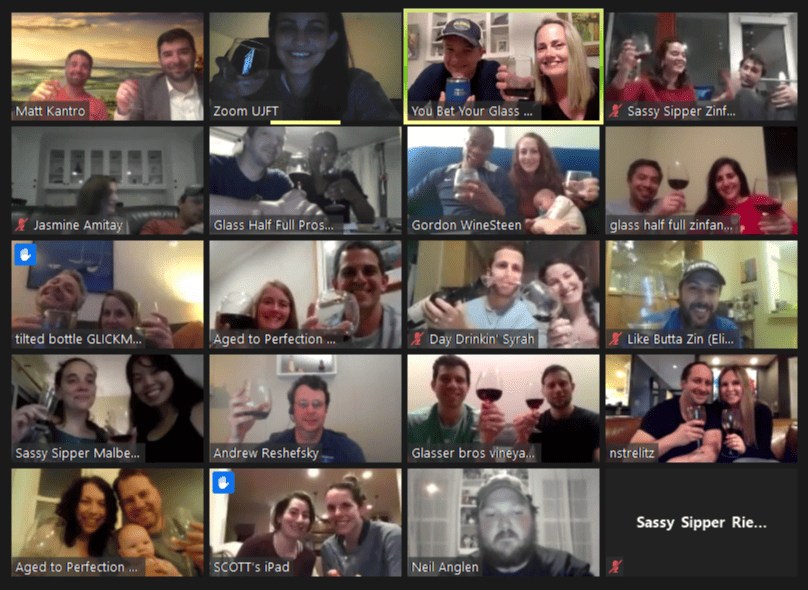

What we’re experiencing right now isn’t a blip on the radar. For many of us, finding transcendent, supportive communities online isn’t some ridiculous pipe dream. We’ve felt it. We’ve shed tears at digital shiva minyanim. We’ve forged close bonds of friendship and connection with people we have never met in-person. In fact, we who have struggled to connect with our local institutions may have found that growing and connecting to Judaism online has been easier than in our on-the-ground neighborhoods.

Perhaps that fact is a challenging thing to hear. Our approach to the digital world has too often been to perceive it as a competitor to “in-person” Judaism and its institutions.

That need not be our attitude. Every Jewish community, all around the world, deserves to be celebrated and supported. And as it turns out, the Jewish community with the largest population today is not in Jerusalem or New York City. It’s the digital Jewish community, with a population numbering many, many millions. So let’s build it together; may digital Judaism become strong—truly strong—and through it may we all be strengthened.

For some Jewish organizations, maybe all of this sounds like heresy. I can’t say that impulse is ludicrous. It’s rare that you can accurately use “always” to describe a historical reality, but Jewish religious and cultural practices have always—always!—been built on shared geographic proximity. Indeed, the very phrase “Jewish community” being ascribed to digital spaces might initially seem like a contradiction in terms.

But will it feel like a contradiction to our grandchildren? Could we begin to craft early versions of digital Jewish experience that grow potentially into fully formed expressions of Judaism in the coming decades and centuries?

My instinct is that we can, but doing so requires us to rethink what a community is and means. If community refers to a set of Jews who share a metropolitan area, then digital work is a challenge. But if community refers to a set of people who are interested in gathering together, supporting one another, sharing life’s moments of sadness and joy, and marking important calendrical times together, that’s achievable online. We just have to adopt that task fully as a Jewish collective in order to make it a reality.

This piece is a part of our series of Visions for the Post-Pandemic Jewish Future—To submit an essay for consideration, email opinion@jta.org with “Visions Project Submission” in the subject line.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of JTA or its parent company, 70 Faces Media.