( JTA)—Jewish tourists from North America are likely to notice one big difference when visiting synagogues around the world. Though a plethora of symbols, such as stars of David and menorahs, may be displayed, national flags are rare inside the sanctuary.

( JTA)—Jewish tourists from North America are likely to notice one big difference when visiting synagogues around the world. Though a plethora of symbols, such as stars of David and menorahs, may be displayed, national flags are rare inside the sanctuary.

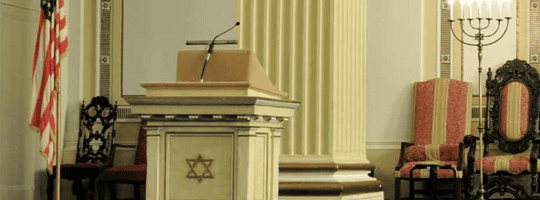

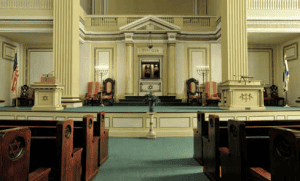

Meanwhile, in the United States and Canada, an American or Canadian flag (and sometimes both) are commonly displayed on the bimah, or ritual stage, often alongside an Israeli flag.

When did this uniquely North American Jewish custom originate and why?

According to historian Gary Zola, it’s due to a patriotic wave during World War I and, later, the birth of Israel.

About a decade ago, a student asked Zola about the history of flags in American synagogues. So Zola, the executive director of the Jacob Rader Center of the American Jewish Archives and a professor at the Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion in Cincinnati, set out to find the answer. That led to a study of the history of the American flag and how it was viewed at different periods in time. He is currently working on an article summarizing his research.

Though the American flag was officially adopted in 1777, when it featured only 13 stars representing the original colonies, it grew in significance in 1814, the year Francis Scott Key wrote what became the national anthem, The Star-Spangled Banner. He composed the song after seeing the American flag flying defiantly above Fort McHenry in Baltimore during the War of 1812. The creation of the anthem ignited “the birth of flag culture,” Zola says.

“The flag then becomes much more than just a banner for identifying things,” he says. “We all are familiar with American eagle, but the American eagle doesn’t resonate with the same kind of deep, deep patriotic feelings that the flag does, and that helps you understand the transformation that takes place as a result of the poem, and the idea that the banner becomes the embodiment of the American people and nation.”

In the following decades, the flag began to be used by politicians as part of their political campaigns and was flown over public buildings, banks, and churches. Zola found evidence of some synagogues at the time being decorated with American flags, though it does not seem to have been ubiquitous.

The Civil War was the flag’s “big transformational moment,” Zola says. At the Battle of Fort Sumter in April 1861, Confederate forces bombed the fort, causing its main flagpole to fall down. The Fort Sumter Flag becomes “the martyr symbol of America,” and was shown all around the North and used to raise money for Union war efforts.

“It becomes the tangible symbol of why they were fighting this war,” Zola says.

The Stars and Stripes were carried into the battle by the Union troops. Following President Abraham Lincoln’s assassination, flags abounded as he was mourned and his body was transported from Washington to his burial place in Springfield, Illinois. Zola found evidence that some synagogues displayed American flags inside the sanctuary as rabbis eulogized the president.

Still, flags were not a permanent fixture in American synagogues until World War I, with the popularization of the service flag, a banner that used stars to symbolize family members who were fighting or killed in the war.

“These service flags, while they were not literally the American flag, they had a familiarity, they had stars on them and they were American colors, and churches and synagogues began to fly those service flags inside the sanctuaries as a tribute to the soldiers and as a patriotic symbol,” Zola says.

This opened the gates to American flags being displayed as a permanent fixture inside synagogues, he says, usually flanking the bimah, the sanctuary’s main stage.

Photos from Jewish confirmation ceremonies in the 1920s and 1930s show American flags in the background, and by World War II , the practice of displaying flags next to the bimah was “almost ubiquitous,” according to Zola.

Still, for some synagogues the decision to add an American flag was triggered by quite a different event: the emergence of Zionism and creation of the state of Israel. After both the Balfour Declaration in 1917 and Israel’s Declaration of Independence in 1948, synagogues wanted to fly the Zionist or Israeli flags. But many members felt that flying a Jewish nationalist flag without an American flag wasn’t right, so they added both.

In most cases, however, the flying of the American flag was not a way for Jews to prove their patriotism, but rather to participate in a defining cultural practice, Zola says.

“American Jews, like in everything else, want to do what Americans are doing. And just as the flag becomes a part of American culture and begins to take on the emotional effect that it has over a period of time, American Jews want to participate,” he says.

Many synagogues didn’t come lightly to the decision to fly a flag. In 1954, Reform Rabbi Israel Bettan declared that Old Glory may hang in an American synagogue on the grounds that devotion to the welfare of one’s country “has long assumed the character of a religious duty.” In 1957, Rabbi Moshe Feinstein, the famed Orthodox authority, said secular symbols like flags had no place in the sanctuary; however, since the display of flags does not violate halacha, or Jewish law, a congregation is not required to remove them.

Synagogues tend to follow the etiquette in the U.S. Flag Code, which says the Stars and Stripes should be placed on the leftmost pole, and the other flag to the right (from the audience’s perspective).

North American Jews are so used to the practice today that they may not realize that to most Jews around the world, a flag seems out of place in a house of worship.

“We are so familiar with this in America, it’s so common whether it’s a Reform synagogue, Conservative, and even some Orthodox [synagogues] that we take it for granted, it’s almost unnoticed, but when you travel the world you begin to realize, ‘Gee, this isn’t the way it is everywhere.’”

– Josefin Dolsten