Passover is a uniquely Jewish holiday, with four cups of wine, matzah, 10 plagues, and the central Seder plate. Though traditions and rituals vary among families and different cultures, the Passover story, retold each year, celebrates freedom during the Exodus from Egypt.

Even in the United States, even in Virginia, even in Tidewater, Passover traditions and seders vary from locale to locale and from home to home. Imagine the differences from country to country!

Five community members share their seder experiences outside of the United States, detailing the foreign cuisine, joyous moods, global themes, and even political ramifications in observing Pesach.

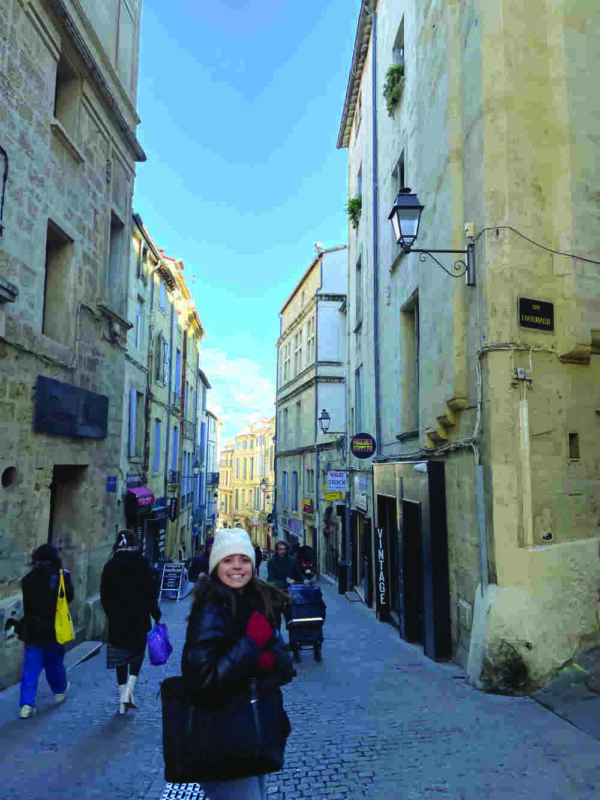

Audrey Peck • France

While studying abroad last year, I unexpectedly ended up at a Passover seder in Montpellier, France with a family I had never met. While my French language skills are not bad, I was grateful to learn that most of them spoke English.

Other than that, and the seder being in French and Hebrew instead of English and Hebrew, the evening was almost identical to the seders I experienced growing up. The family went around the table, each person reading a different part. When it was my turn, they asked if I wanted to read in French, English, or Hebrew. There was not an English option in the Haggadah, so I opted for French.

As the meal was being served, they asked if I knew what gefilte fish was. Again, their meal was almost identical to what I would have been eating at home. For dessert, they served the most delicious kosher for Passover cake I think I’ve ever had.

This family was incredibly welcoming, and it was an evening most people won’t be lucky enough to experience. In typical French fashion, the meal did not start until relatively late, so I finally made it home close to 1:30 am with enough matzah and cake for a month!

Judit Roth • Hungary

In the 1980s, the reality for Jewish families in Hungary was stark. Openly practicing one’s faith was not an option, so we were unable to celebrate Passover. Living under the oppressive shadow of the Iron Curtain, practicing our faith meant risking persecution, discrimination, and much worse.

In Szekesfehervar, the city I grew up in, with no synagogues to gather in and religious education banned, the essence of Passover remained elusive for us. Most of our family members had perished in the Holocaust, leaving us disconnected from our heritage and traditions. In the absence of a vibrant Jewish community, we struggled to maintain our identity in secret, hidden from the prying eyes of authorities and neighbors.

We did receive one box of matzah from Israel each year, and this was quietly distributed by one of the Jewish aid organizations in Budapest. Receiving the matzah was a bittersweet reminder of our faith, delivered clandestinely yet unable to be fully embraced.

One of the driving forces behind my decision to move to the United States was the desire to embrace Judaism, to raise my future children in a community where our faith could be celebrated openly and without fear.

My first seder in Virginia Beach remains a cherished memory. Held at the gorgeous home of Sara and Aaron Trub, with my then in-laws, Dr. Joseph and Rosalee Familant, the seder was a beautifully presented affair, rich with tradition and familial warmth. We took turns reading from the Haggadah, and though I struggled with some pronunciations, the experience was deeply meaningful. From the unfamiliar gefilte fish to the time-honored rituals, every moment felt like a revelation. But what struck me most was the simple joy of being present, openly and proudly Jewish, surrounded by a tight-knit family. It was in that moment that I knew I had made the right decision to move to the United States, where I could embrace my faith without fear and celebrate my heritage with others who understood its significance.

Janice Foleck • England

In England when I was growing up, we began the seder after sunset and ended sometime around midnight. Everyone dressed in their best clothes.

One of the major differences was that everyone had their own Haggadah and no two were the same, so you had to pay attention because everyone was on a different page. We never skipped anything. The service was in Hebrew and led by my grandfather, but we read together as opposed to here where we go around the table. Also, the karpas that we dipped in salt water was potato not celery.

At the age of five, I had to learn the four questions by heart in both languages because I couldn’t read.

The six-course meal was similar to what we have here. One of the things I remember as different was my grandmother would break sheets of matzah into small pieces and soak them in the juice from the homemade gefilte fish. I never remember eating gefilte fish from a jar, always homemade. In England, they make fried, as well as boiled, gefilte fish.

My grandfather made all the Pesach wine in the basement of their house which was used as a Pesach kitchen.

After Elijah’s cup was Grace After Meals. Then the rest of the service, including my favorite part, which was when we sang ALL the songs.

When I started making my own seders, I followed the English pattern and our children and grandchildren now follow many of these traditions.

Naomi Limor Sedek • Australia

The beauty of the Passover Seder is that the retelling is codified. The Haggadoth codify our shared journey from slavery to freedom, the people and their unique experiences sharing space around the table flavor the retelling. My upbringing in an Ashkenazi household centered around cherished traditions like the lively singing of Who Knows One. Upon marrying into my husband’s Sephardic Persian family 26 years ago, I embraced new customs, such as incorporating rice and playfully whipping each other with green onions during Dayenu.

Last Passover, my husband and I traveled across the globe to Australia to visit our daughter who was studying abroad in Sydney for the semester. We reunited with old friends, the Schach family from Nashville, for the first night seder, reminiscent of the comfort and familiarity akin to our ancestors in Egypt.

Our second seder was more kismet. The experience began around the Shabbat table two weeks before our departure in Norfolk at the home of Rashi and Levy Brashevitzky. I knew that we were going to be in Melbourne, Australia on our way to see the penguins in Phillips Island and knew no one in the area. At Shabbat dinner, Rashi’s brother, Levi, was visiting from Israel and we were playing Jewish geography. It so happens his wife, Aidel, has an uncle in Melbourne and connected us. I reached out to her Aunt Michi to see if there was a communal seder in Melbourne that we could attend. She insisted that we join her family as guests around their seder table.

Our second seder in Melbourne epitomized the journey of the Israelites leaving Egypt. Through a serendipitous connection, we found ourselves welcomed into the home of strangers, experiencing the warmth of hospitality, and forming lasting friendships, despite initial uncertainties.

In Sydney, reunited with the Schachs, a unique Passover experience awaited at the Great Synagogue—a chorale concert for the Counting of the Omer. Led by Rabbi Menachem Feldman, the choir’s performance displayed a fusion of Western Jewish choral music, offering a soul-stirring interpretation of tradition.

Despite the vastness of the world, our Jewish family remains interconnected andhospitable. I encourage others to embrace the spirit of exploration, as our ancestors did in their quest for freedom. As we say in the seder, “Next year in Jerusalem.”

Dinah Halioua • Tunisia

The day after our Muslim neighbor approached my father proclaiming to soon marry one of his daughters, my father left Tunis, Tunisia for Paris, France. My mother, sisters, and I soon followed when I was 16 years old.

Three years later, in France, I met my Moroccan husband, Raphael. Raphael’s entire family moved to Virginia where his sister had married an American. In 1969, I came to visit for two months and loved it.

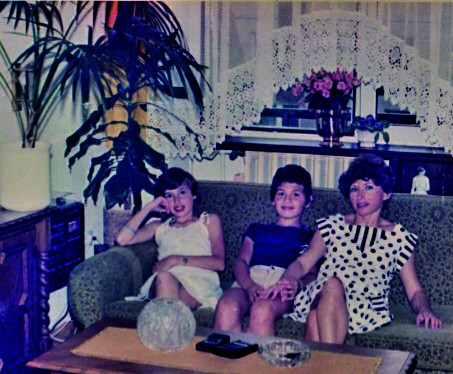

Seders in Tunis were a large, family affair. First night seder was at my grandfather’s house. He was a joyful man with a beautiful voice who loved to sing. The 15 granddaughters would all have a sleepover after the seder. Our second night seder was a smaller event at my other grandmother’s house, with my four uncles and cousins.

Gefilte fish and matzah ball soup were not on the menu. Instead, first night’s dinner began with a vegetable soup, followed by a meat dish stuffed with carrots, fennel, coriander, parsley, and other spices. On the second night, I remember stuffed artichoke with peas served with rice (a Sephardic tradition on Passover) and a kugel-like dish with potato, egg, and chicken.

Raphael’s family traditionally served brains and tongue for the lunches during yontiv, so I prepare Tunisian recipes for the rest of the holiday. Erev Passover, in Tunisia, we did not search for chametz; instead, we had a barbeque and then burned the chametz. I continued this tradition in Virginia when my parents visited from France.

While my family observes both Moroccan and Tunisian customs during Passover, I still use my French Haggadah.

David Wolfe • England

At first glance, we brought our seder traditions with us when we moved from the UK in 1994. The first night has always included friends and family. The second night is typically much smaller and sometimes just the two of us.

Pesach, more than any other time, marks the passage of time and the circle of life. The story stays the same, but the people inevitably change – even if the little, new faces remind us so much of guests of yesteryear.

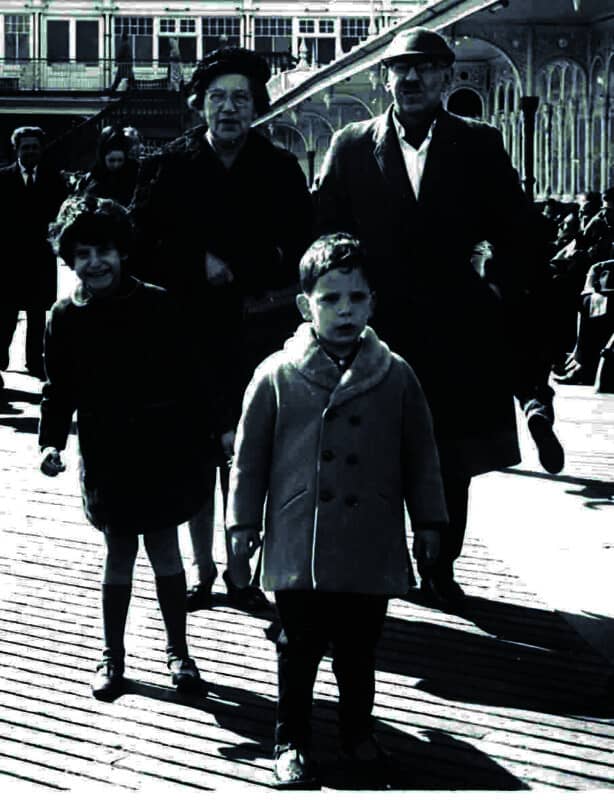

My earliest memories are with my maternal grandparents in Brighton, UK. I was very close to my grandfather, Benjamin, who was born in 1905 in Brooklyn and spent his first four years in New York, before his family moved on and ended up in London. This year, we will complete a 118-year full circle family journey when we travel to New York City to join our two-year old grandson, Jacob, with our daughter and son-in-law, just a couple of miles from where his great, great grandfather celebrated his own second seder.

Pesach is our favorite holiday, with elements that we hope will never change. We will always discuss modern day freedoms. Over the years, we have covered, inter alia, excerpts from The Freedom Writers Diary and MLK’s entire I Have a Dream speech. These texts led to some unforgettable, multi-generational discussions.

Tears will no doubt well-up as we look at our grandson and sing Said the Father, a song about the four sons’ questions that we have sung as a family for as long as we can remember, and we will think about family members seeking freedom from health issues. The perennial cries of “let my people go” and “next year in Jerusalem” will have special meaning, as we pray for the hostages who sadly remind us of the fine line we have always walked between freedom and captivity. Above all, though, Pesach will provide many wonderful memories of guests who have left us and new memories of little ones who now enrich our lives in ways we never imagined possible.

So where did our Pesach traditions come from? I think our ancestors knew a thing or two when they showed us that Jewish traditions are about family and not about geography.

Shelach et ami and Happy Pesach to all.

L’Dor V’Dor.